United States armed forces

| United States Armed Forces |

|

|---|---|

United States Joint Service Color Guard on parade at Fort Myer in Arlington County, Virginia. |

|

| Service branches | |

| Leadership | |

| Commander-in-Chief | President Barack Obama |

| Secretary of Defense | Robert M. Gates |

| Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff | Admiral Michael Mullen |

| Manpower | |

| Military age | 17–45 years old[1] |

| Available for military service |

72,715,332 males, age 18–49 (2008 est.), 71,638,785 females, age 18–49 (2008 est.) |

| Fit for military service |

59,413,358 males, age 18–49 (2008 est.), 59,187,183 females, age 18–49 (2008 est.) |

| Reaching military age annually |

2,186,440 males (2008 est.), 2,079,688 females (2008 est.) |

| Active personnel | 1,473,900[2] (ranked 2nd) |

| Reserve personnel | 1,458,500[3] |

| Expenditures | |

| Budget | $692 billion (FY10)[4] (1st by total expenditure, 27th as percent of GDP) |

| Percent of GDP | 4.7 (2010 est.) |

| Related articles | |

| History | American Revolutionary War Early national period Continental expansion American Civil War Post-Civil War era World War I (1917–1918) World War II (1941–1945) Cold War (1945–1991) Vietnam War (1959-1975) War on Terrorism (2001–present) |

| Ranks | Army officer Army warrant officer |

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. They consist of the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, and Coast Guard.

The United States has a strong tradition of civilian control of the military. While the President is the overall head of the military, the United States Department of Defense (DoD), a federal executive department, is the principal organ by which military policy is carried out. The DOD is headed by the Secretary of Defense, who is a civilian and a member of the Cabinet, who also serves as the President's second-in-command of the military. To coordinate military action with diplomacy, the President has an advisory National Security Council headed by a National Security Advisor. Both the President and Secretary of Defense are advised by a six-member Joint Chiefs of Staff, which includes the head of each of Department of Defense service branches, led by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The Commandant of the Coast Guard is not a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

All of the branches are under the direction of the Department of Defense, except the Coast Guard, which is an agency of the Department of Homeland Security. The Coast Guard may be transferred to the Department of the Navy by the President or Congress during a time of war.[5] All five armed services are among the seven uniformed services of the United States; the others are the United States Public Health Service Commissioned Corps and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Commissioned Corps.

From the time of its inception, the military played a decisive role in the history of the United States. A sense of national unity and identity was forged out of the victorious Barbary Wars, as well as the War of 1812. Even so, the Founders were suspicious of a permanent military force and not until the outbreak of World War II did a large standing army become officially established.

The National Security Act of 1947, adopted following World War II and during the onset of the Cold War, created the modern U.S. military framework; the Act merged previously Cabinet-level Department of War and the Department of the Navy into the National Military Establishment (renamed the Department of Defense in 1949), headed by the Secretary of Defense; and created the Department of the Air Force and National Security Council.

The U.S. military is one of the largest militaries in terms of number of personnel. It draws its manpower from a large pool of volunteers; although conscription has been used in the past in various times of both war and peace, it has not been used since 1972. As of 2010, the United States spends about $692 billion annually to fund its military forces,[4] constituting approximately 43 percent of world military expenditures (As of 2009). The U.S. armed forces as a whole possess large quantities of advanced and powerful equipment, which gives them significant capabilities in both defense and power projection.

Contents |

History

The history of the United States armed forces dates to 1775, even before the Declaration of Independence marked the establishment of the United States. The Continental Army, Continental Navy, and Continental Marines were created in close succession by the Second Continental Congress in order to defend the new nation against the British Empire in the American Revolutionary War.

These forces demobilized in 1784 after the Treaty of Paris ended the War of Independence. The Congress of the Confederation created the United States Army on June 14, 1784, yet for a period the United States did not have a standing army. The 1787 adoption of the Constitution gave the Congress the power to "raise and support armies," "provide and maintain a navy," and to "make rules for the government and regulation of the land and naval forces," as well as the power to declare war and gave the President of the United States the responsibility of being the military's commander-in-chief.

Rising tensions at various times with Britain and France the ensuing Quasi-War and War of 1812 quickened the development of the United States Navy (established October 13, 1775) and the United States Marine Corps (established 10 November 1775). The United States Coast Guard dates its origin to the founding of the Revenue Cutter Service in 1790; that service merged with the United States Life-Saving Service in 1915 to establish the Coast Guard. The United States Air Force was established as an independent service in 1947; it traces its origin to the formation of the Aeronautical Division, U.S. Signal Corps in 1907 and was part of the U.S. Army before becoming an independent service.

Budget

The United States has the largest defense budget in the world. In fiscal year 2010, the Department of Defense has a base budget of $533.8 billion. An additional $130.0 billion was requested for "Overseas Contingency Operations" in the War on Terrorism, and over the course of the year, an additional $33 billion in supplemental spending was added to Overseas Contingency Operations funding.[4][6][7] Outside of direct Department of Defense spending, the United States spends another $218–262 billion each year on other defense-related programs, such as Veterans Affairs, Homeland Security, nuclear weapons maintenance, and the State Department.

By service, $225.2 billion was allocated for the Army, $171.7 billion for the Navy and Marine Corps, $160.5 billion for the Air Force and $106.4 billion for defense-wide spending.[8] By function, $154.2 billion was requested for personnel, $283.3 billion for operations and maintenance, $140.1 billion for procurement, $79.1 billion for research and development, $23.9 billion for military construction, and $3.1 billion for family housing.[9]

In fiscal year 2009, major defense programs also saw continued funding. $4.1 billion was requested for the next generation fighter, F-22 Raptor, which will roll out an additional twenty planes for FY 2009. $6.7 billion was requested for the F-35 Lightning II, which is still in development. Sixteen planes will be built as part of the funding. The Future Combat System program is expected to see $3.6 billion for its development. A total of $12.3 billion was requested for missile defense, which includes Patriot CAP, PAC-3 and SBIRS-High systems. $720 million was also included for a third missile defense site in Europe. $4.2 billion was also requested to continue the aircraft carrier replacement program. With the addition of AFRICOM, $389 million was requested to develop and maintain the new command.[10]

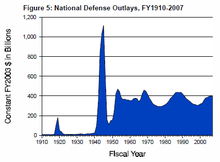

Historically, defense-related spending in the United States is at its highest inflation-adjusted level since World War II. Per-capita spending is at approximately the same inflation-adjusted level as the peak of the late-1980s Cold War military build-up and the 1968 peak of the Vietnam War. In his Fiscal Year 2011 budget, President Obama has proposed a 4% increase in Department of Defense spending, followed by a 9% decrease in FY 2012, with funding remaining level in subsequent years.[4]

Personnel

As of December 31, 2009 1,421,668 people are on active duty[11] in the military with an additional 848,000 people in the seven reserve components.[3] It is an all volunteer military, however, conscription through the Selective Service System can be enacted by the request of the President and the approval of Congress. All males, ages 18 through 25, who are living in the U.S. are required to register with the Selective Service for a potential future draft.

The United States military is the second largest in the world, after the People's Liberation Army of China, and has troops deployed around the globe.

In early 2007, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates proposed to the President to increase the overall size of the Army and Marine Corps to meet the needs of the War on Terrorism.[12] Current plans are to increase the Army to 547,400 and the Marine Corps to 202,000 by 2012. The expansion will cost a total of $90.7 billion between 2009 and 2013 as the Navy and Air Force undergo a limited force reduction.[13] In addition, in 2009, Gates proposed increasing the size of the Army by 22,000 troops in order to reduce fatigue from multiple trips overseas, and to compensate for troops who are in recovery away from their units. The Fiscal Year 2011 Department of Defense budget request [14] plan calls for an active military end strength of 1,406,000, an increase of 77,500 from the 2007 baseline as a result of increments in the Army (65,000 more troops) and Marine Corps (27,100 more troops) strength and decrements in the Navy (13,300 less troops) and Air Force (1,300 less troops) strength.

As in most militaries, members of the U.S. Armed Forces hold a rank, either that of officer, warrant, or enlisted, and can be promoted.

Personnel in each service

As of May 2009[15] Female numbers as of 30 September 2009[16]

| Component | Military | Enlisted | Officer | Female | Civilian |

| 548,000 | 456,651 | 88,093 | 74,411 | 243,172 | |

| 203,095 | 182,147 | 20,639 | 12,290 | ||

| 332,000 | 276,276 | 51,093 | 51,029 | 182,845 | |

| 323,000 | 261,193 | 64,370 | 64,137 | 154,032 | |

| 41,000 | 32,647 | 8,051 | 4,965 | 7,396 | |

| Total Active | 1,445,000 | 1,174,563 | 224,144 | 203,375 | 580,049 |

| 403,616 | |||||

| 205,000 | |||||

| 40,000 | |||||

| 67,000 | |||||

| 107,000 | |||||

| 67,000 | |||||

| 11,000 | |||||

| Total Reserve | 833,616 | ||||

| Other DOD Personnel | 97,976 |

Personnel stationing

Overseas

As of March 31, 2008, U.S. armed forces were stationed at more than 820 installations in at least 135 countries.[18] Some of the largest contingents are the 151,000 military personnel deployed in Iraq, the 71,000 in Afghanistan, the 52,440 in Germany (see list), the 35,688 in Japan (USFJ), the 28,500 in Republic of Korea (USFK), and the 9,660 in Italy and the 9,015 in the United Kingdom respectively. These numbers change frequently due to the regular recall and deployment of units.

Altogether, 77,917 military personnel are located in Europe, 141 in the former Soviet Union, 47,236 in East Asia and the Pacific, 3,362 in North Africa, the Near East, and South Asia, 1,355 are in sub-Saharan Africa with 1,941 in the Western Hemisphere excepting the United States itself.

Within the United States

Including U.S. territories and ships afloat within territorial waters

As of December 31, 2009, a total of 1,137,568 personnel are on active duty within the United States and its territories (including 84,461 afloat).[19] The vast majority, 941,629 of them, were stationed at various bases within the Contiguous United States. There were an additional 37,245 in Hawaii and 20,450 in Alaska. 84,461 were at sea, 2,972 in Guam, and 179 in Puerto Rico.

Types of Personnel

Enlisted

Prospective service members are often recruited from high school and college, the target age being those ages 18 to 28. With the permission of a parent or guardian, applicants can enlist at the age of 17 and participate in the Delayed Entry Program (DEP). In this program, the applicant is given the opportunity to participate in locally sponsored military-related activities, which can range from sports to competitions (each recruiting station DEP program will vary), led by recruiters or other military liaisons.

After enlistment, new recruits undergo Basic Training (also known as boot camp in the Navy, Coast Guard and Marines), followed by schooling in their primary Military Occupational Specialty (MOS)or rating at any of the numerous training facilities around the world. Each branch conducts basic training differently. For example, Marines send all non-infantry MOS’s to an infantry skills course known as Marine Combat Training prior to their technical schools, while Air Force Basic Military Training graduates attend Technical Training and are awarded an Air Force Specialty Code (AFSC) at the apprentice (3) skill level. The terms for this vary greatly, all non-infantry Army recruits undergo Basic Combat Training (BCT), followed by Advanced Individual Training (AIT), while all combat arms recruits go to OSUT, one station unit training which combines basic and AIT, while the Navy send its recruits to Recruit Training and then to "A" schools to earn a rating. The Coast Guard's recruits attend basic training and follow with an "A" school to earn a rating.

Initially, recruits without higher education or college degrees will hold the pay grade of E-1, and will be elevated to E-2 usually soon after the completion of Basic Training. Different services have different incentive programs for enlistees, such as higher initial ranks for college credit and referring friends who go on to enlist as well. Participation in DEP is one way recruits can achieve rank before their departure to Basic Training.

There are several different authorized pay grade advancement requirements in each junior enlisted rank category (E-1 to E-3), which differ by service. Enlistees in the Army can attain the initial pay grade of E-4 (Specialist) with a full four-year degree, but the highest initial entry pay grade is usually E-3 (Members of the Army Band program can expect to enter service at the grade of E-4). Promotion through the junior enlisted ranks occurs upon attaining a specified number of years of service (which can be waived by the Soldiers chain of command), a specified level of technical proficiency, and/or maintenance of good conduct. Promotion can be denied with reason.

Non-commissioned officers

With very few exceptions, becoming a non-commissioned officer (NCO) in the United States military is accomplished by progression through the lower enlisted ranks. However, unlike promotion through the lower enlisted tier, promotion to NCO is generally competitive. NCO ranks begin at E-4 or E-5, depending upon service, and are generally attained between three and six years of service. Junior NCOs function as first-line supervisors and squad leaders, training the junior enlisted in their duties and guiding their career advancement.

While considered part of the non-commissioned officer corps by law, senior non-commissioned officers (SNCOs) referred to as Chief Petty Officers in the Navy and Coast Guard, or staff non-commissioned officers in the Marine Corps, perform duties more focused on leadership rather than technical expertise. Promotion to the SNCO ranks, E-7 through E-9 (E-6 through E-9 in the Marine Corps) is highly competitive. Personnel totals at the pay grades of E-8 and E-9 are limited by federal law to 2.5 percent and 1 percent of a service's enlisted force, respectively. SNCOs act as leaders of small units and as staff. Some SNCOs manage programs at headquarters level and a select few wield responsibility at the highest levels of the military structure. Most unit commanders have a SNCO as an enlisted advisor. All SNCOs are expected to mentor junior commissioned officers as well as the enlisted in their duty sections. The typical enlistee can expect to attain SNCO rank after 10 to 16 years of service.

Each of the five services employs a single Senior Enlisted Advisor at departmental level. This individual is the highest ranking enlisted member within his/her respective service and functions as the chief advisor to the service secretary, service chief of staff, and Congress on matters concerning the enlisted force. These individuals carry responsibilities and protocol requirements equivalent to general and flag officers. They are as follows:

- Sergeant Major of the Army

- Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps

- Master Chief Petty Officer of the Navy

- Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force

- Master Chief Petty Officer of the Coast Guard

Warrant Officers

Additionally, all services except for the Air Force have an active Warrant Officer corps. Above the rank of Warrant Officer One, these officers may also be commissioned, but usually serve in a more technical and specialized role within units. More recently though they can also serve in more traditional leadership roles associated with the more recognizable officer corps. With one notable exception (helicopter and fixed wing pilots in the U.S. Army), these officers ordinarily have already been in the military often serving in senior NCO positions in the field in which they later serve as a Warrant Officer as a technical expert. Most Army pilots have served some enlisted time. It is also possible to enlist, complete basic training, go directly to the Warrant Officer Candidate school at Fort Rucker, Alabama, and then on to flight school.

Warrant officers in the U.S. military garner the same customs and courtesies as commissioned officers. They may attend the Officer's club, receive a command and are saluted by junior warrant officers and all enlisted service members.

The Air Force ceased to grant warrants in 1959 when the grades of E-8 and E-9 were created. Most non-flying duties performed by warrant officers in other services are instead performed by senior NCOs in the Air Force.

Commissioned officers

There are five common ways to receive a commission as an officer in one of the branches of the U.S. military (although other routes are possible).

- Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC)

- Officer Candidate School (OCS): This can be through active-duty OCS academies, or, in the case of the National Guard, through state-run academies.

- Service academies (United States Military Academy at West Point, New York; United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland; United States Air Force Academy at Colorado Springs, Colorado; the United States Coast Guard Academy at New London, Connecticut; and the United States Merchant Marine Academy at Kings Point, New York.)

- Direct commission - civilians who have special skills that are critical to sustaining military operations and supporting troops may receive direct commissions. These officers occupy leadership positions in the following areas: law, medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, nurse corps, intelligence, supply-logistics-transportation, engineering, public affairs, chaplain corps, oceanography, and others.

- Battlefield commission - Under certain conditions, enlisted personnel who have skills that separate them from their peers can become officers by direct commissioning of a commander so authorized to grant them. This type of commission is rarely granted and is reserved only for the most exceptional enlisted personnel; it is done on an ad hoc basis, typically only in wartime. No direct battlefield commissions have been awarded since the Vietnam War. The Air Force and Navy do not employ this commissioning path.

- Limited Duty Officer - Due to the highly-technical nature of some officer billets, the Navy employs a system of promoting proven senior enlisted members to the ranks of commissioned officers. They fill a need that is similar to, but distinct from that filled by Warrant Officers (to the point where their accession is through the same school). While Warrant Officers remain technical experts, LDOs take on the role of a generalist, like that of officers commissioned through more traditional sources. LDOs are limited, not by their authority, but by the types of billets they are allowed to fill. However, in recent times, they have come to be used more and more like their more-traditional counterparts.

Officers receive a commission assigning them to the officer corps from the President (with the consent of the Senate). To accept this commission, all officers must take an oath of office.

Through their careers, officers usually will receive further training at one or a number of the many staff colleges.

Company-grade officers in pay grades O-1 through O-3 (known as "junior" officers in the Navy and Coast Guard in pay grades O-1 through O-4) function as leaders of smaller units or sections of a unit, typically with an experienced SNCO assistant and mentor.

Field-grade officers in pay grades O-4 through O-6 (known as "senior" officers in the Navy and Coast Guard in pay grades O-5 and O-6) lead significantly larger and more complex operations, with gradually more competitive promotion requirements.

General officers, or flag officers in the Navy and Coast Guard, serve at the highest levels and oversee major portions of the military mission.

Five Star Ranking

These are ranks of the highest honor and responsibility in the armed forces, but they are almost never given during peacetime service and are only held by a very few officers during wartime:

- General of the Army

- Fleet Admiral

- General of the Air Force

No corresponding rank exists for the Marine Corps or the Coast Guard. Like three and four-star ranks, Congress is the approving authority of a five-star rank confirmation.

The rank of General of the Armies is considered senior to General of the Army, but was never held by active duty officers at the same time as persons who held the rank of General of the Army. It has been held by two people: John J. Pershing who received the rank in 1919 after World War I, and George Washington who received it posthumously in 1976 as part of the American Bicentennial celebrations. Pershing, appointed to General of the Armies in active duty status for life, was still alive at the time of the first five-star appointments during World War II, and was thereby acknowledged as superior in grade by seniority to any World War II era Generals of the Army. George Washington's appointment by Public Law 94-479 to General of the Armies of the United States was established by law as having "rank and precedence over all other grades of the Army, past or present," making him not only superior to Pershing, but superior to any grade in the United States Army in perpetuity.

In the Navy, the theoretically corresponding rank to General of the Armies is Admiral of the Navy. It was never held by active duty officers at the same time as persons who held the rank of Fleet Admiral. George Dewey is the only person to have ever held this rank. After the establishment of the rank of Fleet Admiral in 1944, the Department of the Navy specified that the rank of Fleet Admiral was to be junior to the rank of Admiral of the Navy. However, since Dewey died in 1917 before the establishment of the rank of Fleet Admiral, the six star rank status has not been totally confirmed.

Demographic controversies

Though women may serve as military police, combat pilots, on combat ships, and, as of 2010, submarines, female service members are prohibited by policy from intentional assignment to certain ground combat forces. (See History of women in the military#United States.)

The "don't ask, don't tell" law (10 U.S.C. § 654) allows homosexuals to serve in the military as long as they do not disclose their sexual orientation; the Government is also not allowed to ask service members or prospective recruits about their sexual orientation. Since the policy was enacted in 1993 by President Bill Clinton, thousands of service members have continued to be discharged when their orientation came to the attention of the military.

Both policies have been the subject of high-profile public controversy in the 1990s and 2000s, with advocates citing military necessity and the special requirements of combat conditions, and opponents denying military necessity and characterizing the policies as unjustified discrimination.

Non-citizens are allowed to join the U.S. military (but not to serve as officers) if they possess a green card. Green card holders are required to register for Selective Service.[20] Those serving are given an expedited citizenship process. Currently, 40,000 non-citizens enlisted with 8,000 enlistments a year.[21][22] Federal law allows application for citizenship after one year of active service and President Bush signed an executive order allowing non-citizens to apply for citizenship after only one day of active-duty military service.[21] A program to recruit a limited number of specially skilled immigrants with only temporary immigration status drew some controversy.[23] Illegal immigrants are not allowed to enlist although some have completed JROTC.[21]

African-American representation in high quality Army recruits has declined by 7.1 percent between 2000 and 2007. The primary factor driving this decrease appears to be the American involvement in the Iraq War.[24]

Representation of numerous religious affiliations is present throughout the branches of the military.[25]

Order of precedence

Under current Department of Defense regulation, the various components of the Armed Forces have a set order of seniority. Examples of the use of this system include the display of service flags, placement of Soldiers, Marines, Sailors, and Airmen in formation, etc.. When the United States Coast Guard shall operate as part of the Navy, the cadets, United States Coast Guard Academy, the United States Coast Guard, and the Coast Guard Reserve shall take precedence, respectively, after the midshipmen, United States Naval Academy; the United States Navy; and Naval Reserve.[26]

- Cadets, US Military Academy

- Midshipmen, US Naval Academy

- Cadets, United States Coast Guard Academy (when the Coast Guard shall operate as part of the Navy)

- Cadets, US Air Force Academy

- Cadets, United States Coast Guard Academy (when the Coast Guard shall operate as part of the Department of Homeland Security)

- Midshipmen, US Merchant Marine Academy

- United States Army

- United States Marine Corps

- United States Navy

- United States Coast Guard (when the Coast Guard shall operate as part of the Navy)

- United States Air Force

- United States Coast Guard (when the Coast Guard shall operate as part of the Department of Homeland Security)

- Army National Guard of the United States

- United States Army Reserve

- United States Marine Corps Reserve

- United States Naval Reserve

- United States Coast Guard Reserve (when the Coast Guard shall operate as part of the Navy)

- Air National Guard of the United States

- United States Air Force Reserve

- United States Coast Guard Reserve (when the Coast Guard shall operate as part of the Department of Homeland Security)

- Other training and auxiliary organizations of the Army, Marine Corps, United States Merchant Marine, Civil Air Patrol, and United States Coast Guard Auxiliary, as in the preceding order.

Note: While the United States Navy is actually older than the United States Marine Corps [27], the Marine Corps takes precedence over the Navy due to previous inconsistencies in the Navy's birth date.[27] The Marine Corps, however, has recognized its observed birth date on a more consistent basis.[27] The Second Continental Congress established the Navy on October 13, 1775[27] and the Marines Corps in November 10, 1775.[27] The Navy did not officially recognize October 13, 1775 as its birth date until 1972 when, then-Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Elmo Zumwalt authorized it to be observed as such.[27]

See also

- Full-spectrum dominance

- United States military academies

- United States military staff colleges

- Awards and decorations of the United States military

- Servicemembers' Group Life Insurance

- TRICARE - Health care plan for the U.S. uniformed services

- List of currently active United States military land vehicles

- List of active United States military aircraft

- List of currently active United States military watercraft

- Uniformed services of the United States

- State Defense Forces

- Military Law

- Military Expression

- Relative costs of American wars

References

- ↑ Persons 17 years of age, with parental permission, can join the U.S. armed services.

- ↑ http://siadapp.dmdc.osd.mil/personnel/MILITARY/ms0.pdf

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=110_cong_bills&docid=f:s3001pcs.txt.pdf

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Federal Government Outlays by Function and Subfunction: 1962–2015 Fiscal Year 2011 (Table 3.2)

- ↑ The United States Coast Guard has both military and law enforcement functions. Title 14 of the United States Code provides that "The Coast Guard as established 28 January 1915, shall be a military service and a branch of the armed forces of the United States at all times." Coast Guard units, or ships of its predecessor service, the Revenue Cutter Service, have seen combat in every war and armed conflict of the United States since 1790, including the Iraq War.

- ↑ Funding Levels for Appropriated (“Discretionary”) Programs by Agency (Table S–11)

- ↑ http://www.gpoaccess.gov/usbudget/fy09/pdf/budget/defense.pdf

- ↑ Death and Taxes

- ↑ Table 3.2—Outlays by Function and Subfunction: 1962–2014

- ↑ http://www.ndia.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Advocacy/Action_Items/FY2009_Major_Weapons_Systems.pdf

- ↑ http://siadapp.dmdc.osd.mil/personnel/MILITARY/history/hst0912.pdf

- ↑ Bender, Bryan (12 January 2007). "Gates calls for buildup in troops". The Boston Globe. http://www.boston.com/news/nation/washington/articles/2007/01/12/gates_calls_for_buildup_in_troops/. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- ↑ http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/2009dodbud.pdf

- ↑ http://comptroller.defense.gov/defbudget/fy2011/FY2011_Budget_Request_Overview_Book.pdf

- ↑ http://www.airforce-magazine.com/MagazineArchive/Magazine%20Documents/2009/May%202009/0509facts_fig.pdf

- ↑ http://siadapp.dmdc.osd.mil/personnel/MILITARY/rg0909f.pdf

- ↑ Lamothe, Dan (Friday October 16, 2009 18:10:12 EDT). "Corps ends year with 203,000 active Marines". Marine Corps Times. Gannett Company. http://www.marinecorpstimes.com/news/2009/10/marine_202Kreached_101609w/. Retrieved 2009-10-17.

- ↑ "Active duty military personnel strengths by regional area and by country" (PDF). U.S. Department of Defense. 2008. http://siadapp.dmdc.osd.mil/personnel/MILITARY/history/hst0803.pdf. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- ↑ http://siadapp.dmdc.osd.mil/personnel/MILITARY/history/hst0912.pdf

- ↑ Conscription in the United States, Selective Service

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Prepared Statement of The Honorable David S. C. Chu, Under Secretary of Defense (Personnel and Readiness) Before the Senate Armed Services Committee, July 10, 2006

- ↑ Through the military, a path to citizenship, Jeff Jacoby, Boston Globe, February 13, 2008

- ↑ U.S. Military Will Offer Path to Citizenship, Julia Preston, New York Times, February 14, 2009

- ↑ Explaining Recent Army and Navy Minority Recruiting Trends

- ↑ Anderson Cooper 360: Religious preference in the military

- ↑ Title 10, United States Code, section 118 (prior section 133b renumbered in 1986); DoD Directive 1005.8 dated 31 October 77 and AR 600-25

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 Precedence of the U.S. Navy and the Marine Corps Department of the Navy -- Naval History & Heritage Command, 04 October 2009

External links

- Official U.S. Department of Defense website

- Global Security on U.S. Military Operations

- Military News

- Today's Military website

- US Military ranks and rank insignia

- Defence Talk

- Center of Defence Information on U.S. Military

- U.S. Military deployments/engagements 1975-2001

- MilitaryForceUSA.org Installation Overviews

- Department of Defense regulation detailing Order of precedence: DoD Directive 1005.8, 31 October 1977 and also in law at Title 10, United States Code, Section 133.

- Army regulation detailing Order of Precedence: AR 840-10, 1 November 1998

- Marine Corps regulation on Order of Precedence: NAVMC 2691, Marine Corps Drill and Ceremonies Manual, Part II, Ceremonies, Chapter 12-1.

- Navy regulation detailing Order of Precedence: U.S. Navy Regulations, Chapter 12, Flags, Pennants, Honors, Ceremonies and Customs.

- Air Force regulation detailing Order of Precedence: AFMAN 36-2203, Drill and Ceremonies, 3 June 1996, Chapter 7, Section A.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||